(from Sewanee magazine, Fall 1997)

The sound comes without warning. The air splits as though someone ripped a piece of tent canvas overhead, loud enough to feel it in the ribcage. A photographer ducks and someone curses. Overhead, with power, streaks a high–tech dart in blue and yellow chasing five others distant to form up with them in a triangle: the leader in front, two behind him, two—now three—in the rear. The six F/A–18 hornets climb together until they fade into the haze, a distant delta pattern imprinted on the sky like a moving wallpaper motif, climbing and arching into a loop. Directly above and on their backs—inverted—they begin their plunge, still in formation and accelerating, with white smoke tracing the trajectory. Faster, faster, there! The six split at equal angles in curving downward paths, the smoke tracing what looks like an upside down trumpet bell. As a plane turns tight for the next maneuver, water vapor flashes over the wings in shock waves, a phenomenon of lift, speed, and high humidity. One observer smiles and nods.“Okay vapes,” he says.

Navy Lt. Bryan Buchanan points at one of the jets, following it, making mental notes which he quickly jots onto a file card, looking again into the Pensacola sky to acquire them for the next maneuver.

Over the runway, the U.S. Navy’s Blue Angels flight demonstration squadron has been practicing their dangerous aerial ballet: soaring, climbing, zooming—sometimes as close as 21 inches cockpit–to–wing—sometimes playing chicken at a combined head–on airspeed of nearly 1,000 knots, sometimes in incredibly tight turns boosting a pilot’s relative weight to nearly 1,500 pounds—seven–and–a–half gravities, or“G’s”—for 19 seconds. And Lt. Buchanan scrutinizes each maneuver for form and function, jotting notes for the critique that follows each performance.

He has been watching the Pensacola sky since he was six, when he and his brother would pilfer their father’s binoculars and sit on the roof to watch the Blue Angels practice over the nearby naval air station. Now his brother is a commercial pilot and Bryan is flight surgeon to the elite navy squadron he idolized as a boy.

Buchanan is 33, single, and sometimes wowed by his job with “the Blues.” He is as outwardly confident as the pilots he calls his patients, showing almost teenage enthusiasm accented by an Audie Murphy aw–shucks smile. Those he works with say he is a good fit here, and just like his pilots, Buchanan is at the top of his career as flight surgeon.

In the second floor offices in the Blue Angels hangar, Buchanan’s modest clinic is better than average as flight surgeons go, he says—roughly eight feet by 14 feet in basic navy gray. In the corner is a gray medicine cabinet with stainless steel and glass doors. Gray’s Anatomy is on one shelf, tongue depressors and gauze jars sit on another. The examination table takes up the lion’s share of space. His clipboard bears the name “Witch”—one of Buchanan’s earlier call signs—short for witch doctor. Along with Buchanan’s desk is another near the window for his corpsman, “Baby Doc.” Ever present is the high–pitched whine of jet engines. The window overlooks eight blue and yellow jets sitting on the tarmac, canopies open, maintenance men polishing the Plexiglas.

Officially, Buchanan serves first as both team physician and Marcus Welby for the Blue Angels pilots and staff. In addition to learning about average human maladies, military flight surgeons have to recognize effects of high altitude and high speed flight—positive G’s pushing the blood out of your head and to your feet, negative G’s where everything’s going up to your head pulling you out of your seat, hypoxia, disorienting conditions changes in air pressure, and other causes and effects with exotic, barely pronounceable names—along with the psycho–physical stress of performing on the edge.

After graduation at Sewanee, Buchanan attended medical school at the University of Alabama as a naval reservist, the navy picking up the tab through a highly competitive scholarship program. While average medical school students dream about country clubs and a two story colonial near the third tee, Buchanan says he couldn’t wait to get into a fighter, and the navy is the only branch of service requiring flight surgeons to go through flight training. “It was really tough. It gave me a lot of insight into what these guys go through preparing.”

Buchanan said he entered flight school with “a little bit of attitude.”

“I said, ‘Hey, I went through Sewanee, I went through comps, I went through medical school, and doggone it I’m gonna whip this in the pants’—I studied my butt off.

“I had a little runway set out in my living room and I would walk around the room and make all my calls. Every flight is an oral exam. You get quizzed before you fly then you go crawl into the plane.” Then, Buchanan says, the “90 percent rule” comes into play: “Ninety percent of what you knew on the ground leaves you. You kinda go ‘bla–h–h–h’ and you’re working on monkey skills.”

While Buchanan trained in a standard navy turbo–prop T–34, he isn’t qualified to pilot the high–performance jets his charges fly. He hitches a ride in a two–seat variant of the F/A–18 whenever he can, and sometimes they’ll let him take the stick in the back seat for a while flying between air shows.

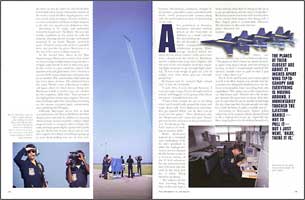

“My orders call for duty involving flying. One of the ways I get a better feel for what they’re doing in the air is to go up with them and see what it looks like.” Buchanan says he has flown with several pilots at his various duty stations, but flying with a Blue Angels pilot is considerably different. The first time he flew with the four–plane diamond formation [there are also two soloists] was in New Orleans last year. “The planes at their closest are about 21 inches apart wing–tip–to–canopy and everything is moving around. I momentarily touched the ejection handle—not to pull it—but I just went, ‘Okay, there it is.’”

The F/A–18, used by navy and marine pilots as well as the Blue Angels, is so nimble that the manufacturer designed inhibitors into the airframe to keep pilots from exceeding their own capabilities. “The planes can really outperform us,” Buchanan said. “Therein lies a bit of danger because the guys have to know what they can do and what the jet is capable of and keep the two close together. Certain people can take G’s a little bit better. It adds a variable into it.”

According to Buchanan, fighter pilots today have to be in peak athletic physical form to fly a high–performance jet, especially the Blue Angels pilots who fly without benefit of a G–suit—standard issue to fighter pilots to counteract high G–forces in tight turns. Special pockets in the G–suit thighs unpredictably inflate and could bump the extra–sensitive control stick during close formation flying. The Blue Angels pilots control upper body blood flow during high–G turns by grunting loudly and repeatedly—like dry heaves in rhythm—to force blood back to the head and avoid blacking out. While Buchanan says the technique has been around since there have been jets, he oversees a rigorous weight training program to keep the Blue Angels pilots in top form.

Even a common cold can give a pilot a bad day. “There was a case overseas of a pilot who had a sinus infection and he kept it secret. His cabin pressurization wasn’t working well and he blew a sinus. He had to have surgery and he was out of the cockpit for almost a year,” Buchanan says. “If he’d have just kept things in perspective he could have been flying probably in seven days or sooner.”

Military pilots are traditionally wary of doctors since they have the power to ground them. A visit for something seemingly minor can have a pilot flying a desk. In his book The Right Stuff, author Tom Wolfe says high performance pilots look at flight surgeons as “natural enemies.” Marine Major Pat Cooke, the number two pilot clockwise in the diamond, agrees with the stereotype, but says professionalism and his relationship with Buchanan keep things in balance. “Everybody is wary of bringing a problem up to their flight surgeon. At the same time, we know—especially here at the Blue Angels—you come second to the overall team. If I were to fly knowing I had a medical problem…I would really be selling my teammates short.

“Most flight surgeons fit in very well in the squadron life,” Cooke, a former Top Gun instructor, says. “They’re about the same age, they share the same interests. Most of the fleet pilots feel very comfortable with their doctors. Hopefully, you’ve got confidence in your flight surgeon that he’s not going to see one of those red flags go up and take you out of the ball game early.”

Buchanan said grounding a pilot is the “least favorite” part of his job, and he believes in the relationship he has with the pilots. “I feel like they tell me what’s going on with their lives. I flew on every type of mission my squadrons flew. I was there at weddings, at a funeral, when folks got promoted, when folks had birthdays. It’s my job to be there all the time—to be an integral part of the squadron, so if they see me sliding into second base at a softball game, it builds up a trust.

“I have the most contact with any of the pilots. I share a car with number two. When we go to winter training we live next door to each other. I am the community doctor. The more I see the more it helps me see. My door is always open.”

Rian Dom, wife of the lead pilot, navy Cmdr. George Dom, says Buchanan goes out of his way to take care of the pilots and their families. “There have been times when family members have been sick and the minute he gets off the C–130 or out of the back seat he is at their door. He’s pretty exceptional.”

Buchanan says his career puts in contact two type A personalities that are very much alike. “Pilots have their checklists, their briefing procedures;they’re very methodical. Physicians are as well. You have a checklist for symptoms on a patient, a checklist for your differential diagnosis, and you try to compartmentalize things.”

As a flight surgeon, Buchanan sizes up pilots, knowing what traditionally makes a successful naval aviator. A good pilot has to have a healthy dose of attitude to be worth his salt. “You want somebody in the air who’s gonna think he’s the baddest one in the skies…‘Yea though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death I will fear no evil ’cause I’m the baddest flyer in the valley.’ One of my pilots in another squadron would strut around and say that, but he could back it up. He routinely out flew air force F–15s north of Japan.

“Most of these guys [the Blue Angels] have either been students or instructors at Top Gun, or been adversary pilots at adversary squadrons. One guy is the out–of–control flight expert for the Tomcat. The boss [Dom] has flown combat missions in Libya and Desert Storm. Four of the guys flew in the Gulf War.”

With that set of credentials, Buchanan is careful about his choice of words as one of the flying team’s official critics. During performances, Buchanan stands next to a communications cart watching every move, marking observations, and picking the formation out of the haze to cue the team videographer. After the routine, the pilots and observers critique the show, Buchanan lending a spectator’s eye view. “Does the smoke come on at the same time? When they go up is anyone out of position? I was awful when I first started. I said, ‘Hey, blue jets in the sky! They look beautiful!’”

Now, he looks at the note cards and has the jargon down. “Go down to the double farvel [an actual term derived from “fabulous” and “marvelous”] where number one and number four are inverted and you’ve got neat perspective on that…for the double farvel they had matched timing on the roll in but four overbanked and climbed. The smoke was okay…When they climbed out and pushed down on the stick…they did a mismatched turn so their wings weren’t matched…” Sometimes the critiques are tough and the pilots question the call, but the video is there to back him up—or prove him wrong, which, Buchanan says happens on occasion. Cooke says Buchanan’s critiques are valuable to him and his teammates. “I’m not going to go up to a Van Gogh and look at it two feet away, I’m going to step back and look at it. His perspective is the one that’s the most valuable. I want to see [the performance] unfold as the team.”

The hardest part of the job is the travel, sometimes at the pace of a rock star, says Buchanan. “I love it, but it gets hard after a while. My parents still live here in town. I’ve seen them for a total of 40 minutes this week. When you go on the ship, it’s a six month cruise and then you’re home. We’re traveling 300 days out of the year, so it’s like being on a cruise for two years.

“I come back [from traveling] and have a science experiment growing in my refrigerator. I have tons of laundry. I really don’t have anybody to help me do that, but by the same token I don’t have anybody I’m leaving behind 300 days out of the year. I don’t have to call the kids and say, ‘Oh, Daddy’s in Fargo, or San Francisco this weekend.’

“I talked to an old suitemate of mine who went straight into residency and I did this, and I told him, ‘I’m a little envious because you’ve got the house and the family.’ And he cut me off and said, ‘Yeah, but look at what you’re doing.’” ⊗

©1997 The University of the South